Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

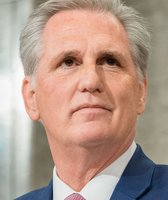

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis at a news conference along the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass, Texas, on June 26, 2023. (AP)

If Your Time is short

- Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a leading contender for the Republican presidential nomination, released an immigration platform June 26 in which he pledged to end birthright citizenship, the automatic granting of citizen status to anyone born on U.S. soil.

- Then-President Donald Trump also proposed doing that in 2018, though he never formally followed through.

- Legal experts say that anything short of a constitutional amendment seeking to end birthright citizenship would prompt a major court battle. Supporters of keeping birthright citizenship can make a strong case, experts say, though it’s possible that courts could side with opponents of birthright citizenship.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a leading contender for the Republican presidential nomination, released an immigration platform June 26 in which he pledged to end birthright citizenship, the automatic granting of citizen status to anyone born on United States soil.

In his platform, DeSantis said he would "take action to end the idea that the children of illegal aliens are entitled to birthright citizenship if they are born in the United States."

If the idea of ending birthright citizenship sounds familiar, it’s because then-President Donald Trump proposed doing it in 2018. However, Trump never followed through with official action, earning him a Promise Broken from PolitiFact.

When Trump initially proposed overturning birthright citizenship through an executive order, legal experts told PolitiFact that it couldn’t be done easily and that the most an executive order would do is prompt a high-stakes court battle. Depending on how the courts ruled, overturning birthright citizenship might necessitate a constitutional amendment, a much more daunting hurdle.

We asked a half-dozen legal experts whether the obstacles to ending birthright citizenship had changed since 2018. They agreed that they hadn’t.

Here’s an explanation of what birthright citizenship is and how it would need to be overturned.

The notion of birthright citizenship can be traced back to 1608 with Calvin’s Case, a British decision that became part of the common law adopted in the U.S. legal system’s early days. Calvin’s case granted subjectship — a British concept that has since evolved into citizenship — to all children born in Scotland except those of diplomats and enemy troops in hostile occupation.

Three key pieces of legal precedent underpin birthright citizenship, scholars say.

First, there’s the Constitution's 14th Amendment, which says that "all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside."

This amendment, ratified in 1868, "was unquestionably intended to cover the children of unauthorized migrants, namely the children of enslaved persons brought here by criminals after the prohibition of the slave trade," said Gabriel (Jack) Chin, a law professor at the University of California, Davis.

Second, there’s an 1898 Supreme Court decision, known as the Wong Kim Ark case. Wong Kim Ark, a laborer, was born in 1873 in San Francisco. His parents were of Chinese descent but lived legally in the United States.

Around age 17, Wong left for a visit to China and returned to the United States without incident. Then, around age 21, he left again to visit China, but at the end of that trip, he was denied reentry to the United States because the collector of customs argued that he was not a U.S. citizen. (This was no small distinction — it was the era of anti-immigrant strictures known as the Chinese Exclusion Acts.)

In its 6-2 majority decision, the Supreme Court’s justices ruled that Wong — and others born on United States soil, with a few clear exceptions — did qualify for citizenship under the 14th Amendment.

"The Fourteenth Amendment affirms the ancient and fundamental rule of citizenship by birth within the territory, in the allegiance and under the protection of the country, including all children here born of resident aliens. … The Amendment, in clear words and in manifest intent, includes the children born, within the territory of the United States, of all other persons, of whatever race or color, domiciled within the United States," the court’s majority wrote in its decision.

Third, there’s a 1952 statute (8 U.S. Code § 1401) that echoes the language in the 14th Amendment. "The following shall be nationals and citizens of the United States at birth: (a) a person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof," the statute partly reads.

Peter J. Spiro, a Temple University Law School professor, said the "consistent, systematic, and unbroken historical practice" of birthright citizenship would itself be a strong argument for keeping it in place.

"For at least a century, the government has extended citizenship to the children of parents present in the United States in violation of the immigration laws," Spiro said. "That practice counts for purposes of constitutional interpretation and statutory interpretation."

The wiggle room for universal birthright citizenship’s opponents involves the qualifier "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" — wording that appears in both the constitutional amendment and the statute.

Traditionally, this phrase has been interpreted to exclude only the U.S.-born children of foreign diplomats or of enemy forces engaged in hostilities on U.S. soil. But people skeptical of birthright citizenship’s legal basis have argued that the Supreme Court has never specifically ruled on whether the children of illegal immigrants would qualify for birthright citizenship, since that wasn’t at issue in the Wong Kim Ark case.

The same uncertainty holds for the drafters of the 14th Amendment, legal experts say. "Because there weren't any federal immigration controls at the time the amendment was adopted in 1868, there's no direct evidence how the drafters intended it to apply to that category," Spiro said.

In our 2018 article, we noted that a leading skeptic of birthright citizenship was John C. Eastman, then a law professor at Chapman University.

Eastman had written that undocumented immigrants, like foreign tourists, "are subject to our laws by their presence within our borders, but they are not subject to the more complete jurisdiction envisioned by the Fourteenth Amendment as a precondition for automatic citizenship," he wrote.

Therefore, Eastman argued, the ruling in Wong Kim Ark "does not mandate citizenship for children born to those who are unlawfully present in the United States."

Now, five years later, Eastman is undergoing disbarment proceedings in California related to his legal strategy that argued then-Vice President Mike Pence could have interfered with the certification of Joe Biden’s presidential victory on Jan. 6, 2021. Pence did not interfere, and Eastman’s legal strategy is considered a prelude to the storming of the U.S. Capitol that day by supporters of outgoing President Donald Trump.

Even in 2018, legal scholars disagreed with Eastman’s logic.

"Illegal aliens and their children are subject to our laws and can be prosecuted and convicted of violations — unlike diplomats, who enjoy certain immunities, and unlike foreign invaders, who are generally subject to the laws of war rather than domestic civil law," Ilya Shapiro wrote for the libertarian Cato Institute. "The illegal immigrants’ countries of origin can hardly make a ‘jurisidictional’ claim on kids born in America, at least while they’re here. Thus, a natural reading of ‘subject to the jurisdiction’ suggests that the children of illegals are citizens if born here."

Even if overturning birthright citizenship by statute were possible, the notion that an executive order could accomplish it is dubious, legal experts said.

"If it's mandated by the Constitution, it can only be undone by a constitutional amendment," Spiro said. "If it's mandated by statute, it can only be undone by a subsequent statute. It's only if it's mandated by neither that (a president) could do it by executive order."

The most that DeSantis, or Trump, could do on his own is sign an executive order with the clear expectation that opponents would sue to block its implementation, said Kermit Roosevelt, a University of Pennsylvania law professor. Then, birthright citizenship’s fate would be in the courts’ hands.

The president would effectively be "offering his interpretation" in an executive order, and this "tees up the lawsuit that will get the Supreme Court to rule, once and for all, what it means," said Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a group that generally supports a tighter immigration system.

This type of battle would be analogous to what Biden did in issuing an executive order that lifted a portion of debt for student loan borrowers. Plaintiffs quickly sued to stop Biden’s policy from being carried out, and the Supreme Court is expected to rule on the case soon.

In his immigration platform, DeSantis did not specify how he would seek to bring an end to birthright citizenship. But Never Back Down, the political action committee supporting his presidential bid, referred PolitiFact to a clip of DeSantis discussing Trump’s proposal with CBS Miami in 2018.

In the exchange, DeSantis — then making his initial bid for governor — acknowledged that the legal grounding for birthright citizenship was significant but added that "it has never been finally determined whether someone who’s just transiently in the country, whether as a tourist or here illegally, whether the 14th amendment would apply to them."

DeSantis added, "I do think it would be good to have the court finally resolve it. I don’t know that (Trump) could do it by executive order. But obviously if he did do it, it would be tested immediately and he would get a resolution."

Our Sources

Ron DeSantis, immigration agenda, June 26, 2023

Ron DeSantis, clip from an interview with CBS Miami, 2018

Donald Trump, remarks in an interview with Axios, Oct. 30, 2018

WhiteHouse.gov, Remarks by President Trump before Marine One departure, Oct. 31, 2018; Presidential Actions

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898)

John C. Eastman, "We can apply the 14th Amendment while also reforming birthright citizenship," Aug. 24, 2015

Jon Feere, "How Trump could change birthright citizenship," June 21, 2015

Ilya Shapiro, "Is birthright citizenship constitutionally required?" Aug. 20, 2015

New York Times, "President Wants to Use Executive Order to End Birthright Citizenship," Oct. 30, 2018

Associated Press, "Trump adviser faces possible disbarment over his efforts to overturn 2020 election," June 20, 2023

PolitiFact, "Rand Paul says legality of birthright citizenship not fully adjudicated due to facts of 1898 case," Sept. 18, 2015

PolitiFact, "House bill introduced to end birthright citizenship," April 21, 2017

PolitiFact, Can Donald Trump end birthright citizenship with an executive order? Probably not, Oct. 30, 2018

PolitiFact, "Donald Trump falls short on promise to end birthright citizenship," July 15, 2020

Email interview with John C. Eastman, law professor at Chapman University, Sept. 17, 2015

Email interview with Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, Oct. 30, 2018 and June 28, 2023

Email interview with Jennifer M. Chacón, professor at the UCLA School of Law, Oct. 30, 2018

Email interview with Kermit Roosevelt, law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Oct. 30, 2018

Email interview with Denise Gilman, co-director of the immigration clinic at the University of Texas Law School, Oct. 30, 2018 and June 27, 2023

Email interview with Kevin R. Johnson, dean of the University of California, Davis law school, Oct. 30, 2018 and June 27, 2023

Email interview with Peter J. Spiro, law professor at Temple University Law School, Oct. 30, 2018 and June 27, 2023

Email interview with Gabriel (Jack) Chin, a law professor at the University of California-Davis, Oct. 30, 2018 and June 27, 2023

Email interview with Steve Yale-Loehr, law professor at Cornell University, June 27, 2023

Email interview with Ilya Somin, law professor at George Mason University, June 27, 2023