Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

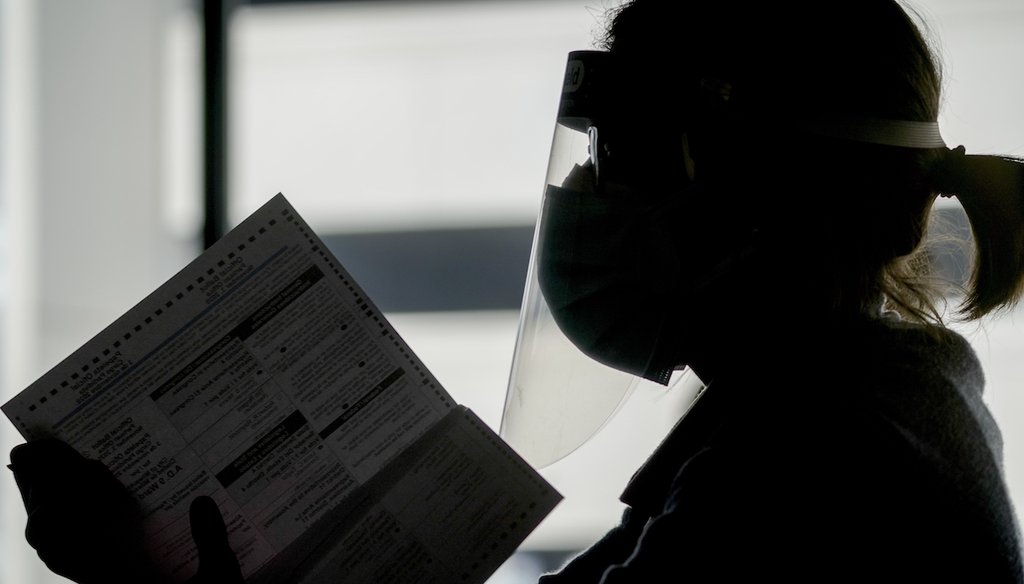

In this Nov. 3, 2020, file photo, workers count Milwaukee County ballots at Central Count in Milwaukee. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

The day-to-day operations of elections are largely funded through city and county dollars. Costs include running voting sites and mailing out and processing absentee ballots.

-

When the pandemic hit in 2020, election offices couldn’t afford new expenses to safely hold elections. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg donated grant money.

-

A Republican backlash has led to state bans on private funding for future elections. Local elections offices risk not having enough money for the 2022 cycle.

As the presidential election approached in 2020, the elections clerk in Boone County, Missouri, had a problem. A federal grant early in the pandemic had helped pay for unexpected election expenses such as plexiglass shields and cleaning supplies at polling places. But that money was now gone, and Election Day was a couple of months away.

"We were looking at it and saying, ‘We do not have the budget for this,’ " said Brianna L. Lennon, the Boone County clerk.

The solution came in the form of a grant of about $500,000 from the Center for Tech and Civic Life. The center is funded by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan.

"Without the additional grant funds, we would not have been able to purchase necessary safety and cleaning supplies, inform voters about changes to the election process or hire the number of additional temporary staff to serve voters," Lennon told PolitiFact.

The Center for Tech and Civic Life distributed $350 million in grants for election to 2,500 jurisdictions like Boone County in 2020.

"To be clear, I agree with those who say that government should have provided these funds, not private citizens," Zuckerberg wrote in October 2020.

Since then, Republican state lawmakers have made every effort to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

Nearly a dozen Republican-led states have banned private donations for election administration, and more bans are under consideration. Denouncing "Zuckerbucks" for election offices has become part of the GOP playbook for candidates running for local, state and federal offices.

Republican groups and politicians objected to Democratic strongholds getting the largest amounts of money, although every jurisdiction that applied received money. Grants ranged from $5,000 for small townships to the largest grant of $19 million for New York City.

Independent election experts generally agree that it’s best for the government, rather than the private sector, to pay for expenses associated with elections.

But the bans on private funding have highlighted a problem known by election experts long before the pandemic: Election administration faces financial strains.

The Zuckerberg money was vital for election officials during the pandemic, said Matthew Weil, an elections expert at the Bipartisan Policy Center. Without the funding, many more jurisdictions would have had delayed reporting of results, which would have further contributed to misinformation.

Still, local election officials are not expecting grants to cover future elections.

"It’s not sustainable to expect philanthropy to step in here," Weil said. "Government at all levels must step up to support the democracy Americans expect."

To understand how elections are funded, look back to 2000, the year that the presidential results were held up for weeks in Florida while officials struggled to interpret old-fashioned punch ballots with hanging chads.

In 2002, with bipartisan support, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act to give states money to replace outdated election equipment and create minimal standards for voter registration databases.

As a result of that law, Congress appropriated about $3.3 billion between 2003 and 2010. Additional funding in fiscal years 2018 and 2020 provided another $805 million.

The 2020 pandemic relief package known as the CARES Act included $400 million in election funding. But that wasn’t enough to provide all of the new pandemic-related election expenses.

The fact that thousands of local offices run in-person voting sites and send out mail ballots may seem inefficient, but it’s a benefit for election security, because it makes it virtually impossible for someone to rig a national election.

But it also means that election funding is largely reliant on local budgets, competing for dollars with other services like parks, libraries and public safety.

Kathleen Hale, an Auburn University political scientist and co-author of the book "How We Vote," examined data from six states and found that on average for all of the counties, the county election office budget is .05% of the total county budget.

"I call that underfunded," Hale said.

State reimbursement varies and never covers the cost of any election, Hale said.

"Election offices run on a shoestring — so yes, additional funding in 2020 was needed for all sorts of changes that were being made to the way elections were conducted," Hale said. "Everything from more paper for ballots, more scanners to scan mailed ballots and signature verification tools."

Zuckerberg said he was stepping in to fill a gap in funding

Citing the higher expenses of holding elections during a pandemic, Zuckerberg announced Sept. 1, 2020, that it would provide $250 million in election grants through the Center for Tech and Civic Life for local counties to pay for staff, training and equipment. A month later, Zuckerberg gave another $100 million. The center posted IRS tax forms that show how much was given to each jurisdiction, but not specifics about how the money was spent.

PolitiFact contacted a handful of local offices to find out.

-

In Licking County, Ohio, a Republican area easily won by Trump, about $77,000 went toward new electronic poll books that elections workers used to check in voters at the polls.

-

In Brevard County, Florida, where voters overwhelmingly voted for Trump, election officials spent about $840,000 on machines and technology used at the polls and for mail ballots.

-

In Palm Beach County, Florida, a left-leaning county where Trump cast his ballot, the roughly $6.2 million went toward various expenses including personal protective equipment, cameras for the elections warehouse, vote-by-mail processing equipment, and TV ads giving voters information about in-person and mail voting.

-

In Coldwater Township, Michigan, the office used $5,000 to purchase two laptops and tech support to run electronic poll books on Election Day, and to pay for extra staff hours.

Critics of the funding said that the largest amounts went to areas with high numbers of Democratic voters, such as cities in Wisconsin where Milwaukee, Racine, Kenosha, Green Bay and Madison received a combined $8.8 million.

In Wisconsin, a George W. Bush appointee, U.S. District Court Judge William C. Griesbach ruled that the grants may "merit a legislative response," but there was nothing in statutes that prohibited cities from accepting the grants. Griesbach noted that in addition to those five cities, over 100 additional Wisconsin municipalities received the grants, and that plaintiffs didn’t challenge any specific expenditures.

Judges in other cases reached similar conclusions about the grants, and some also rejected arguments by some plaintiffs that the grants would drive up turnout by Democrats.

Conservatives who opposed the funding also pointed to the political leanings of the founders of the Center for Tech and Civic Life. The center was founded by three people who previously worked together at a left-leaning digital think tank. (Their current board is bipartisan, and Google and Facebook are among the funders.)

Republican leaders and pundits said the money was used by Zuckerberg to interfere with or "take over" local election offices. Trump later said that the money amounted to election "meddling," while Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said the money was used to "commandeer local election offices in key areas."

But if meddling to benefit Democrats was the goal, then it was a strange strategy to provide the money to every single jurisdiction that applied. There were no partisan questions in the grant applications, and the funding decisions were not made on a partisan basis, said center director Tiana Epps-Johnson, in a statement to PolitiFact.

"Needs differed vastly from election department to election department based on both how jurisdictions changed their voting program during the pandemic and also their previous funding levels," Epps-Johnson said. "Many larger urban areas, for example, required capital-intense investments to count a large volume of absentee and mail ballots in a short period of time, tasks that can often be done at lower cost with less equipment (sometimes even by hand) in the smallest jurisdictions."

Election officials told us that the money did not create outside influence on operations.

In Licking County, Ohio, the decision to use grant money to purchase equipment was made by a bipartisan board, a Republican deputy director and Democratic director.

"There has been no type of partisan agenda attached to it, no type of attempt to control what we are doing with the money," said Luke Burton, the county’s election director and a Democrat. "It did nothing but help our voters."

But some election officials said it’s a better policy for the government rather than the private sector to provide funding.

"Regarding funding future elections, my preference would be for local election offices to receive robust state and federal funding so that outside grants would be rendered unnecessary," said Lennon, the Boone County clerk.

Nonpartisan election experts also raised concerns about the concept of private funding for elections.

"Private philanthropy is just that — private," said Hale, the election administration expert at Auburn University. "Private goals, agendas, and processes are not determined with public input, and are not subject to public scrutiny, or held accountable to the public in any way. And that's as it should be for private funds. That's the history of American philanthropy. But not for money spent on the machinery of democracy. Private funding in this arena is profoundly undemocratic, and elections should not be subject to the influence of private philanthropy."

Following the 2020 election, Republican state legislators sought various ways to rewrite election laws. Eleven states banned private funding: Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, North Dakota, Ohio, Tennessee and Texas. Governors who are Democrats in Wisconsin, Michigan and North Carolina vetoed bans.

The bans say that election officials can’t accept donations of private funding for election administration, although they can use donated space. The strength of the bans varies:— Kansas makes accepting private money a felony, while North Dakota’s law makes it a misdemeanor and carves out an exception of food donations for election workers. Tennessee allows donations of pens and hand sanitizer, while Texas allows donations up to $1,000 with consent from the secretary of state.

More bans are under consideration this year in Alabama, Alaska, Kentucky, Missouri, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia.

The bans have left some election officials befuddled.

Adam Wit, the Republican clerk in Harrison Township, Michigan, said his jurisdiction received nearly $12,000 to increase pay for some workers and bring in part-time staff to handle a record number of absentee ballots.

"I guess I’m confused," Wit said, according to the Detroit Free Press. "Usually, people applaud when their local government gets grants to help offset some of the costs."

Generally the bans on private funding have not been accompanied by legislation to increase funding for elections, though some state lawmakers said they are talking about it.

Michigan State Rep. Ann Bollin, a Republican, said she has discussed committing state dollars for equipment, training and updating the voter rolls. In recent years, Michigan has faced increased election costs to implement the 2018 constitutional amendment that added no-excuse absentee voting and same-day registration.

"I do not think we should allow third-party monies in any way to come into the election process because I think they are an obligation of the government, and government dollars should pay for them," Bollin said.

Wisconsin state Sen. Kathy Bernier, a Republican and former election clerk, has floated the idea of the state providing 50 cents per capita for each municipality and 50 cents per capita for each county. Bernier told 60 Minutes that the presidential election in Wisconsin was clean and fair, and that widespread fraud is all but impossible in Wisconsin.

Bernier criticized some communities for using grants for what she said were unnecessary expenses, such as a mobile voting truck.

"They bought bells and whistles with their money, so to argue they didn’t have enough money to run the election is a bogus argument," Bernier said. "Every election is already in the budget. Would they like more and better? Yep, and that’s what they bought."

Many Democrats in Congress as well as secretaries of state have written to President Joe Biden asking him to include $5 billion for election equipment and security in his next budget proposal.

Some elections offices need to upgrade their equipment, including ballot tabulators and ballot marking devices at polling sites, and voter registration databases, said Donald Palmer, a commissioner on the federal Election Assistance Commission.

"Their systems are obsolete," Palmer said. "They want to upgrade them, but they just can't, because they don't have resources."

One of the main expenses for elections offices again this year will be costs associated with voting by mail.

Election offices face rising costs of paper products, particularly envelopes and instructional inserts that accompany mail ballots, said Jeff Ellington, CEO of Runbeck Election Services, which provides ballots to jurisdictions in more than a dozen states.

The cost "is definitely higher than 2020," said Ellington. "Paper is in very short supply across the country, and not just ballots."

Elections officials have to start the process earlier to purchase ballots and come up with a back-up plan if their primary supplier can’t meet their needs, said Palmer, who was nominated by Trump to the commission in 2019.

"The bottom line is, they will end up paying more money to make sure the demand is met," Palmer said.

RELATED: What can the federal government do right now to protect voting rights before the 2022 midterms?

RELATED: Republicans facing off in 2022 GOP primaries are running ads claiming the 2020 election was stolen

CLARIFICATION We updated the story on March 2 to clarify that money from Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg and wife Priscilla Chan to help with elections came from the couple themselves.

Our Sources

Congressional Research Service, The Help America Vote Act of 2002 (HAVA): Overview and Ongoing Role in Election Administration Policy, Oct. 28, 2021

Congressional Research Service, The Help America Vote Act and Election Administration: Overview and Selected Issues for the 2016 Election, Oct, 18, 2016

National Conference of State Legislatures, 2021 Legislative Action on Elections, Jan. 5, 2022

National Conference of State Legislatures, Which states have limited or prohibited private funds in elections? Aug. 30, 2021

National Conference of State Legislatures, Election Costs: What States Pay, Aug. 3, 2018

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook post, Sept. 1, 2020

Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook post, Oct. 13, 2020

Election Assistance Commission, Election security funds for 2018-2020

Harris County Elections, Tweet, Oct. 12, 2020

APM Media, How private money helped save the election, Dec. 7, 2020

AP, Zuckerberg’s cash fuels GOP suspicion and new election rules, Aug. 8, 2021

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Republicans move to ban election administration grants, Feb. 3, 2022

Washington Post, Election experts sound alarms as costs escalate and funding dwindles, Feb. 16, 2022

Palm Beach Post, Red, white and blue redo of county's ballot counting warehouse fit for HGTV, Nov. 2, 2020

Center for Tech and Civic Life, Final Report on 2020 COVID-19 Response Grant Program and CTCL 990s

Center for Tech and Civic Life, 10 Facts About CTCL & the COVID-19 Response Grant Program, Oct. 14, 2021

Center for Tech and Civic Life, CTCL Partners with 5 Wisconsin Cities to Implement Safe Voting Plan, July 7, 2020

Wall Street Journal editorial page, Zuckerbucks Shouldn’t Pay for Elections, Jan. 3, 2022

Columbia Missourian, Song, video promo for Boone County Clerk’s Office encourages voter education, Oct. 30, 2020

Detroit Free Press, Michigan clerks criticize GOP's proposals for election changes, April 9, 2021

Voting Rights Lab, State voting rights tracker (bills enacted restrictions on private grant money), 2021

Brennan Center for Justice, Voting Rights Litigation Tracker 2020, July 28, 2021

Palm Beach County board of commissioners, Agenda item summary, April 6, 2021

Robert Canterbury, candidate for Maricopa County board of supervisors, Tweet, Feb. 17, 2022

U.S. District Court eastern district of Wisconsin, Wisconsin Voters Alliance et al vs cities of Racine, Milwaukee, Kenosha, Green Bay and Madison, Sept. 24, 2020

Rev.com, Donald Trump CPAC 2021 Speech Transcript Dallas, Texas, July 11, 2021

Detroit Free Press, Michigan clerks concerned Secure MI Vote petition could have far-reaching impact, Nov. 19, 2021

William C. Griesbach, United States District Judge, Order in Wisconsin Voters Alliances vs City of Racine, Oct. 14, 2020

60 Minutes, In Wisconsin, a political battle over the 2020 vote still rages, March 13, 2022

Statement from Tiana Epps-Johnson, founder of the Center for Tech and Civic Life, Feb. 22, 2022

Telephone interview, Wendy Sartory Link, Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections, Feb. 24, 2022

Email interview, Brandon Lorenz, spokesperson for the Center for Tech and Civic Life, Feb. 18, 2022

Email interview, Matthew Weil, director of the elections project at the Bipartisan Policy Center, Feb. 18, 2022

Email interview, Kimberly Boelzner, spokesperson for Brevard County Supervisor of Elections in Florida, Feb. 17, 2022

Telephone interview, Luke Burton, director of the Licking County, Ohio elections office, Feb. 18, 2022

Email interview, Brianna L. Lennon, county clerk in Boone, Missouri, Feb.17, 2022

Telephone interview, Diane Morrison, Coldwater Township, Michigan clerk, Feb. 17, 2022

Telephone interview, Donald Palmer, chair of the Election Assistance Commission, Feb. 22, 2022

Telephone interview, Michigan State Rep. Ann Bollin, Feb. 2022

Telephone interview, Wisconsin state Sen. Kathy Bernier, Feb. 21, 2022

Telephone interview, Jeff Ellington, CEO of Runbeck Election Services, Feb. 18, 2022